Meta Williams stands in a screened-in kitchen on a sunny fall day. She grabs a bowl and throws in flour, baking powder, and salt without measuring.

“I’ve been doing this for a long time,” she says.

Williams has also spent a long time making up for lost time. At age 8 she was taken from her family near Carmacks. She says that when she returned to visit as a teenager, she had much to relearn.

“My mother asked me to make bannock, but it had been years since I had watched anyone. I had to throw everything into a bowl from what I partially remembered. It turned out kind of flat, but my mother didn’t say anything. She was very kind. She just thanked me, buttered it, and ate it.”

Remembering and reconnecting with her Southern Tutchone culture became central themes for Williams, and core to the creation of Kwäday Dän Kenji, or Long Ago Peoples Place. The camp, set up on 400 square metres of Champagne and Aishihik First Nations settlement land, is a place where visitors can see, touch, and taste history, and a testament to pre-contact life.

Remembering and reconnecting with her Southern Tutchone culture became central themes for Williams, and core to the creation of Kwäday Dän Kenji, or Long Ago Peoples Place. The camp, set up on 400 square metres of Champagne and Aishihik First Nations settlement land, is a place where visitors can see, touch, and taste history, and a testament to pre-contact life.

Kwäday Dän Kenji features a mix of meadow and forest encircled by a caribou fence. On arrival, visitors are greeted by a pair of huge, friendly camp dogs. A trail winds past a trapline cabin, a bone cache, a smokehouse, a traditional fish trap—an arrow shaped basket made from willow—as well as a deadfall trap, built from several logs set at an angle and designed to crush medium-sized game lured in by bait. The buildings on the property represent the life of Yukon First Nations over time, as well as a modern adaptation of a traditional tent-shaped Njel. Visitors can also learn the old ways of catching gophers using a noose made of sinew attached to a stick.

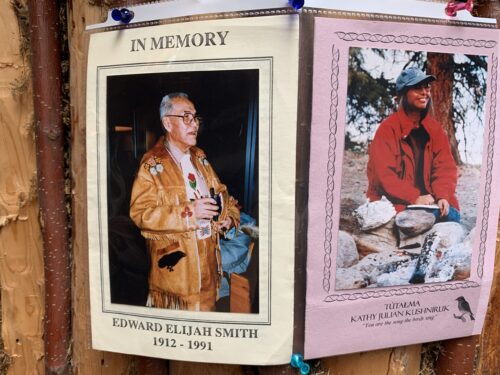

Williams and her partner, Harold Johnson, have spent the past thirty years on this land building, learning, and experimenting in an effort to make the traditional Yukon First Nations ways of life tangible to visitors. Williams brings the bannock, butter, jam, and coffee into the Talking House. The building is big enough to host school and tour groups, and has even been used as an entertainment venue. The walls are made of fir with moss and thinner alder filling the gaps, they are decorated with the names and photos of Elders.

We sit around a long table and Johnson explains that the desire to create Long Ago Peoples Place came from spending time on the land as a child and from his persistent curiosity about how things were done in the old days.

We sit around a long table and Johnson explains that the desire to create Long Ago Peoples Place came from spending time on the land as a child and from his persistent curiosity about how things were done in the old days.

“Every time I got to speak with Elders, I would always direct the conversation to their grandparents, and how people survived,” he says. “Over time, without knowing it, when you grow up that way you accumulate a lot of knowledge.”

Johnson and Williams started, in 1995, by building a skin house. It was modelled on a winter dwelling traditionally made with seven layers of caribou skins atop a wooden frame, creating natural pockets of insulation within the walls, a wicking system to keep out the moisture, and a fire inside for extra warmth.

They learned as they went and relied on the a core group of 12 to 15 Elders.

“Sometimes they would come with materials and say, ‘we’re going to build this today,’ and whatever you were doing at that time was not actually important,” says Williams. “You’d stop what you were doing and just follow them.”

Johnson says the camp—which has become a learning centre in its own right—wouldn’t exist without the contributions of those Elders. In their three decades welcoming community members and visitors, Johnson and Williams have also nurtured its future leaders. Between them they have three children, and seven grandchildren.

Each has grown up, to some degree, at Long Ago People’s Place, and Williams says, time spent at the camp has revealed each of their gifts.

“One of our granddaughters can take any kind of event and break it down so you can see how it’s all going to unfold,” says Williams. “Her twin loves to make things. He built a bunch of outhouses and has experimented with solar power and heaters because that’s what he likes to do.”

Their youngest daughter, Whitney Jonhson-Ward, has the gift of language and is currently taking her third year of an intensive Southern Tutchone immersion program in nearby Haines Junction. She will take her parents’ place and shepherd the camp into the future.

Johnson and Williams say they will both stay involved and will also take a step back.

They have plans to continue teaching and learning. Johnson says he’ll continue to work on building projects. His skills will come in handy as plans for the camp’s expansion get underway. Just like his grandfather, Field Johnson, he also intends to travel the land on horseback.

Williams wants to get back into making dog-packs and blankets. She’d also like to start cooking her bannock in the old way instead of using vegetable oil to accommodate the dietary needs of visitors.

“I’ve been feeling like I need to make time for things that I want to do but haven’t had time for. I want to start cooking with gopher fat again.”

This article was published in the Winter2025 issue of The Yukon Magazine.