When you drive north on Vancouver Island’s Highway 19, keep your eye out for a sign marking Ginger Goodwin Way as you approach the town of Cumberland. That road sign has been there since 2019, although the name was originally given to that stretch of road when the highway opened in 1996. The local MLA in 2001 removed the sign. Why so much fuss over a road sign? May 1st, International Workers Day is a good sign to tell the story of a man who died for his commitment to improving the lives of his fellow workers and his refusal to bear arms in a war he didn’t believe in.

Let’s begin the story in the second half of the 1800s, when advertisements and recruiters in English coal mining towns promised higher wages in British Columbia’s booming mining industry. The journey was dangerous – around Cape Horn, through the Panama Canal, or trudging across the continent – and ended with a notoriously a gruelling and dangerous job. Albert Goodwin, didn’t get to BC until 1910. He was 23 by then, with nine years of mining already under his belt. He was short and stocky and had a shock of red hair upon his head, hence the name, Ginger.

That same year, James Dunsmuir sold two coal mining companies to Canadian Collieries Ltd. He had inherited these from his father, Robert, who left Scotland in 1851 to work for the Hudson’s Bay Company on Vancouver Island. Dunsmuir would go on to stake a claim on 1,600 acres of land, becoming the richest man in British Columbia, owning some two million acres and enjoying an income of an estimated $1000 per day.

James Dunsmuir carried on his father’s legacy of hard work and opposition to organized labour. Both men were willing to use their political influence to crush attempts at unionization – using blacklists, law and order (government militias), racial divisions and scabs to break strikes. Never in 42 years of owning coal mines did they recognize a union or agree to limiting the working days of their employees to eight-hours. James, in particular, is viewed as being responsible for one of the most fatal mining disasters in BC history.

The Dunsmuir’s coal mines may have been in different hands by 1910, but their management’s anti-union stance and disregard for the health and safety of their workers persisted among the business owners. The one concession the miners had gained over the years was the authority to inspect the mines and report safety hazards before beginning work. This did not prove to be a favourable concession, as miners who reported unsafe conditions often ended up getting fired for doing so.

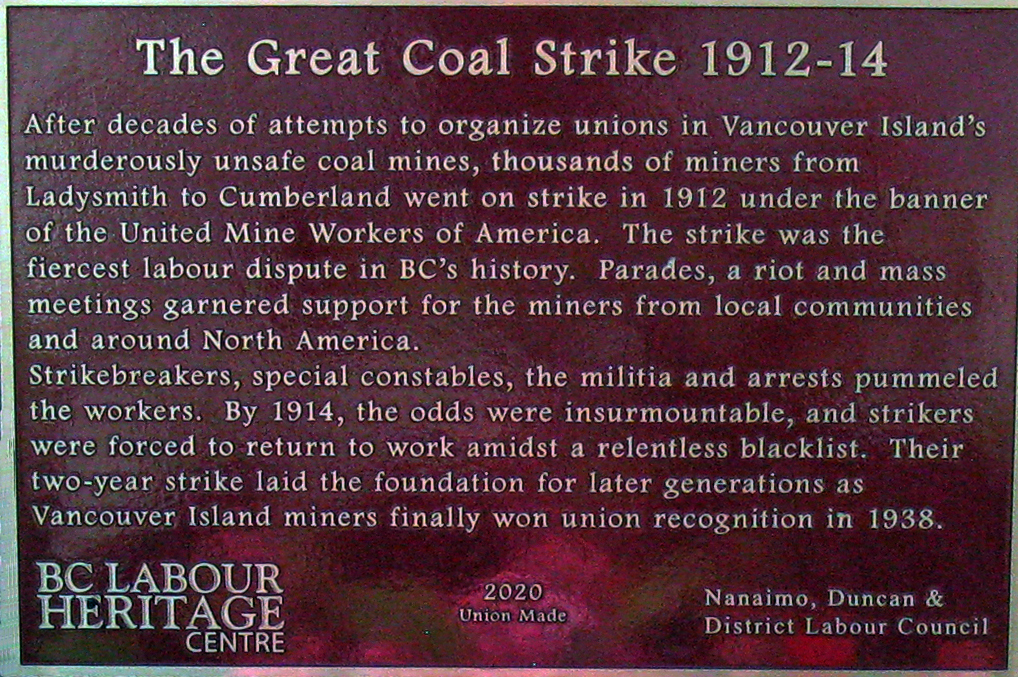

In 1912, miners in Cumberland declared a one-day holiday in support of a man named Oscar Mottishaw, who lost his job for reporting noxious and flammable gas in one of the mines. Canadian Collieries responded by asking the Cumberland miners to remove their tools from the mine and insisting that all of them sign two-year contracts with no change to wages or conditions. The one-day holiday quickly culminated into what would go down in history as one of the most fiercely fought labour disputes in BC history. More than 3,000 miners on the island joined the strike, even though doing so forced them to live in tents through the winter, as their homes were owned by the company. The mining company threatened local workers of Chinese and Japanese origin with eviction from their homes if they did not continue working – and brought in scabs from the US and UK to keep up production. When rioting broke out in August of 1913, Attorney General William Bowser sent a militia of 1000 men with 24,000 rounds of ammunition to subdue the miners. Standing strong in numbers, the miners didn’t give up until the following summer – a month after the United Mineworkers of America withdrew strike pay, and two weeks after the outbreak of war in Europe.

Ginger Goodwin was a recognized labour leader by this point, and was not welcomed back by the power barons at Canadian Collieries Ltd. He took temporary road work for a while before drifting into the interior and landing a new job in mining. As a member of the Socialist Party of BC and vice-president of the BC Labour Federation, he spoke openly about rejecting capitalism and the belief that the war in Europe was fuelled by greed. Ulcers, rotten teeth and “a bit of TB” saved Goodwin from conscription.

In November, 1917, Goodwin led a strike of 1,500 workers with the Mill and Smeltermen’s Union in Trail, BC. They wanted an eight hour day (as opposed to nine) and a wage increase. Eleven days into the strike, Goodwin learned that his status of “unfit for service” had been changed to “fit for combat.” After unsuccessfully appealing the change, he traveled back to Cumberland to seek refuge in the woods with a group of other war resisters. Local labour activists supported the resisters by bringing food and supplies, and Goodwin’s safety was ensured for a time by the support of Cumberland’s police constable. But the province was under pressure to provide more soldiers for the war effort, and sent out special police forces to track down war resisters.

On July 27, 1918, a disgraced police constable named Dan Campbell, joined these forces. Campbell came face to face to face with Ginger Goodwin that day – apparently he was on a trail picking blackberries. Campbell shot him in the neck and claimed that Goodwin had raised his rifle, making the shooting an act in self-defence. This was never proven, but it didn’t seem to matter because charges of manslaughter against Campbell were dropped. He never went to trial.

Cumberland miner’s stopped the police from taking Goodwin’s body out of town and a procession of several thousand people accompanied his coffin to the local cemetery. On that day, August 2, 1918, BC miners walked off the job. Stevedores, transit, construction, shipyard and many other workers across the province joined them. This day marked Canada’s first general strike.

Every June, people in Cumberland still gather at Goodwin’s grave to hold a vigil for him as part of a larger event commemorating the nearly 300 men who died working in local mines.

The same weekend that the government re-instated the highway sign dedicated to Ginger Goodwin, someone defaced his grave, filing off the red hammer and sickle that was etched upon it. Clearly, Ginger Goodwin’s story matters enough that there are people willing to go out of their way to conceal it. As far as I know, there’s never been an open conversation about why the road sign was taken down in 2001. So I am left to assume that a man who put principles before money and pushed against the levers of power to make life a little better for those around him does is not considered worthy of admiration by the powers at be.

Tributes to the Dunsmuirs include a village, a private island, a point (dedicated to Robert’s wife, Joan), and several streets. There’s a town on Vancouver Island named for Attorney General William Bowser who, by the way, not only brought in the military to subdue striking workers but also orchestrated Canada’s first racially-motivated internment policy.

Meanwhile, in the past two years, Canada has seen six statues of John A. MacDonald toppled, alongside monuments commemorating numerous architects of residential schools, monarchs and a bar owner who married a twelve year-old. The status quo, thankfully, is shifting. And there has never been a better time for it.